Maps of the Megamachine | Part II | Amazon

Part II of XX | dataism, ecommerce, strange loops, systems, self, internet of things, algorithms, automation, choice architecture |

We may be a retailer, but we are a tech company at heart. When Jeff started Amazon, he didn’t start it to open a book shop.ᶦ

— Werner Vogels, Amazon CTO (2016)

I. Childhood

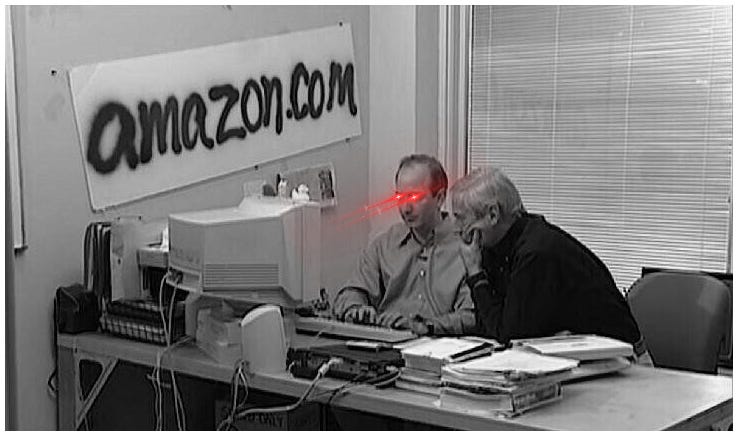

In late October, 1994, an Albuquerque-born computer scientist was on the hunt for a word: a name. Relentless sounded a little too aggressive; Cadabra sounded a little bit too much like cadaver. Exasperated, Jeff Bezos turned to the dictionary and, opening the A section, dragged his thirty-year-old soul back to square one.

The exasperation was short-lived.

On the 1ˢᵗ of November, Bezos registered a new URL; one which linked to nothing more than a world-historical vision. In foetal form, Amazon.com was live.ᶦᶦ

This is not only the largest river in the world, it’s many times larger than the next biggest river. It blows all other rivers away.ᶦᶦᶦ

— Jeff Bezos, Interview with Brad Stone (early 2010s)

On the 3ʳᵈ of April, 1995, Amazon sold its first book: a hardback copy of Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought, written by the theoretical-physicist-turned-literary-sensation Douglas Hofstadter. Once a theoretical physicist at Yale, Jeff Bezos also arrived on the scene to sensational effect: the culmination of a decade-long journey through the worlds of IT, FinTech and D. E. Shaw & Co. (a hedge fun with a strong emphasis on mathematical modelling).

II. Adulthood

Three decades later, according to industry suppliers, Amazon accounts for somewhere between 70 to 80 percent of book sales domestically,ᶦᵛ and somewhere around 67 percent of ebook sales globally.ᵛ

Despite swallowing the market, however, books have come to represent less than 10 percent of the Borgesian, ever-bifurcating revenue streams of The Everything Store.ᵛᶦ

Over the course of the 2010s, returning to Vogels, Amazon has switched channels from goods to services, swiftly and rather silently. Today, as Amazon has sweeps through the 2020s, product sales account for less than half of company profits, as the largest cashflows now stem from a database or (to quote Amazon) a data lake of third-party sellers, third-party advertisers, subscribers to Prime, and subscribers to the cloud storage facilities of Amazon Web Services (AWS)—a dendrite that is already larger than Amazon was a decade ago.ᵛᶦᶦ

…all that is solid melts into PR.ᵛᶦᶦᶦ

— Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism (2009)

Platforms don’t look like how they work and don’t work like how they look.ᶦˣ

— Benjamin Bratton, The Stack (2015)

Instead of creating or commissioning cultural content to be sold to consumers, their main sources of revenue include advertising (Google, Baidu, Facebook), selling hardware at a premium (Apple, Samsung), or e-commerce and cloud hosting (Amazon, Alibaba).ˣ

— Thomas Poell, David B. Nieborg & Brooke Erin Duffy, Platforms and Cultural Production (2021).

III. Livelihood

In swapping out books for data—retail for data—Amazon has positioned itself as a megamachine of decision-making: no longer merely the king of A/B testing,ˣᶦ but a sprawling empire of experimentation, which surveys 525-million square feet of warehouses and data centres,ˣᶦᶦ 40 percent of domestic ecommerce,ˣᶦᶦᶦ and 33 percent of the global cloud.ˣᶦᵛ

The sun never sets over the empire of Amazon. Indeed, much like the edge of our ever-expanding universe, light cannot keep up.

Despite the metaphor, however, Amazon is more algocratic than monarchical: more a “horseless carriage”ˣᵛ or “self-driving company”ˣᵛᶦ than the handsfree Skynet of some thirty-year-old computer scientist, or some fifty-year-old venture capitalist.

In 2012, speaking at the Direct Marketing Association conference, Chris Anderson contrasted the dataism of Amazon with the idealism of Apple, a company with an overarching, overbearing philosophy of marketing and design. At the opposite end of spectrum, Anderson contended, Amazon was unphilosophical to its core: data-driven to the nᵗʰ degree.ˣᵛᶦᶦ

In a letter to shareholders from 2015—“Big Winners Pay for Many Experiments”—Jeff Bezos touched upon the super-efficient, sharp-edged, Seeing Like a State-esque nature of the company:

You can write down your corporate culture, but when you do so, you’re discovering it, uncovering it—not creating it.ˣᵛᶦᶦᶦ

In the seven years since, Amazon has only grown more difficult to put into words.

Random forests, naïve Bayesian estimators, RESTful services, gossip protocols, eventual consistency, data sharding, antientropy, Byzantine quorum, erasure coding, vector clocks: walk into certain Amazon meetings, and you may momentarily think you’ve stumbled into a computer science lecture.ˣᶦˣ

— Jeff Bezos, “Fundamental Tools” (2010)

IV. Parenthood

In every sense of the phrase, front to back, Amazon is a machine: a megamachine of unprecedented scale and specificity, whose currency is no longer the chosen product, but choice itself.

In even starker contrast to Apple, a company that has made a habit of never bending to the will of its usership, Amazon lists “Customer Obsession” as its first and foremost Leadership Principle.ˣˣ From the very beginning, explains former VP Adrian Agostini, the mantra of Jeff Bezos and former co-CEO Sebastian Gunningham has been that all selection is good selection:

They wanted rules in place: don’t offend, don’t kill, don’t poison. Other than that, you take what you get and let customers decide.ˣˣᶦ

Like the nondescript design of the Kindle, the endgame of Amazon has always been “to get out the way.”ˣˣᶦᶦ

To do so, Amazon has pursued the outer limits of algorithms, automation, and architecture. It is a pursuit that led Amazon to become one the first ecommercial players to explore recommendation systems in the early 1990s, swerve from physical to digital media in the early 2000s, switch tracks from retail to technology in the early 2010s, and ride the coattails of Moore’s Law ever since.

V. Neighbourhood

Like Amazon, the origins of this series can be traced to Douglas Hofstadter. In the preface to the twentieth-anniversary edition of Gödel, Escher, Bach, Hofstadter opens with a question: “What is a self, and how can a self come out of stuff that is as selfless as a stone or a puddle?”ˣˣᶦᶦᶦ

It was a question whose answer would arrive eight years later, when Hofstadter published I Am a Strange Loop: a four-hundred-page appraisal of ‘strange loops,’ the complex systems of self-reference that scaffold the sense of ‘I.’ In the ensuing fifteen years or so, the loops have grown stranger still.

In the classic essay “More Is Different,” Philip W. Anderson describes how systems can become so complex that, suddenly, quantitative differences become qualitative ones—boiling water becomes steam.

Psychology is not applied biology, nor is biology applied chemistry.ˣˣᶦᵛ

— Philip W. Anderson, “More Is Different” (1972)

Nor is humanity applied machinery (no matter how mega).

As Web 1.0 has phase-shifted into Webs 2.0 and 3.0, more has certainly become different. Within the digital milieu of the Internet of Things and Bodies, the ‘I’ loops in mysterious ways. It loops in ways more mysterious than the metamagical themas (Hofstadter’s anagram for ‘mathematical games’) that frequent the pages of I Am Strange Loop—a book that, despite its complexity, approaches ‘the self’ via language, perception and cognition: which is to say, addresses ‘the human’ on human terms.

That is a courtesy no longer paid by the mathematical games of today, however, whose leap from qualia to quanta has not only ripened conditions for the end of theory,ˣˣᵛ but the end of theorists.

Moreover, hyperconnected and hyperlinked, the ‘I’ rarely loops alone. If Douglas Hofstadter were to ever write a sequel, We Are a Strange Loop would surely be the title. For while the ‘I’ loops more strangely than before, the ‘we’ loops stranger still.

E-commerce has always been in the reality business, yet the reverse engineering of customer histories can only reveal so much. By assembling, analyzing and acting upon the networked futures of customer data, Amazon is ushering in a new era of behavioural economics—one that lends new weight to the old words of Hannah Arendt:

The trouble with modern theories of behaviorism is not that they are wrong but that they could become true.ˣˣᵛᶦ

Akin to the industrialization of moderation, which Tarleton Gillespie has analysed so deeply and dutifully,ˣˣᵛᶦᶦ the industrialization of recommendation is scaling and systematizing biases at levels unforeseen, unseeable.

VI. Likelihood

Focusing on Amazon’s homegrown algorithms and choice architectures, the following collection of essays will attempt to add clarity to the blurred and blurring line between man and machine: a grey area, which is rendering mesolevel decision-making more and more susceptible to the microtransactional storage and the macroeconomic steerage of the megamachine.

How is megamachinery of Amazon changing the face of human agency?

In search of answer, with introductions out of the way, the remainder of this series will unfold as follows:

I. Breaking down the theory and practice of recommendation systems, I will attempt to describe the ecosystemic properties of the Internet of Recommendations (IoR), which stretches from the unboxed worlds of the Internet of Things (IoT) and the Internet of Bodies (IoB) to the blackboxed worlds of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI).

II. Laying out the concept of desire lines, I will detail how the storage capacities of Big Data and the steerage capabilities of the IoR has created the ideal laboratory conditions for the reverse and real-time engineering of consumer choice.

III. Circling back to the notion of strange loops, I will illustrate how the choice architecture of Amazon has paved the way for recommendation systems to become forces of habit: a laboratory of positive reinforcement, whose instruments of mass- and hyper-personalization have rendered gut feelings and algorithmic nudges increasingly difficult to pick out from a lineup.

IV. Mapping out the idea of dark logistics, I will look at how the entanglements of desire lines and strange loops are paving the way for new forms of path dependence: social and technical, horizonal and nearby.

V. Looking to the near and distant future of human agency, I will try to blueprint the long-term threats and short-term rewards, which threaten to loop decision-making around the maypole of the present—as selfless as a stone or puddle.

In the 1990s, casino tycoon Steven Wynn made a bold claim: “Las Vegas exists because it is a perfect reflection of America.” Since then, writes Natasha Dow Schüll, a rich debate has ensued as to whether America is becoming more like Las Vegas or, alternatively, Las Vegas is becoming more like America; more the like the Western world writ large.ˣˣᵛᶦᶦ

In the 2020s—at least, as far as the mirroring of the Western world is concerned—perhaps Las Vegas needs to step aside.

Narcissus has a new pool.

Be a hero…

Be a god…

References

ᶦ Natalie Berg & Miya Knights, Amazon (Kogan Page: London, 2019), 20.

ᶦᶦ Brad Stone, The Everything Store (New York: Random House, 2013), 35.

ᶦᶦᶦ Ibid.

ᶦᵛ Porter Anderson, “US Publishers, Authors, Booksellers Call Out Amazon’s ‘Concentrated Power’ in the Market,” Publishing Perspectives, 17 August 2020. https://publishingperspectives.com/2020/08/us-publishersauthors-booksellers-call-out-amazons-concentrated-power-in-the-book-market.

ᵛ Max Lakin, “Which eBook Publishing Platform Is Best?” Magnolia Media Network, 20 March 2020. https://magnoliamedianetwork.com/ebook-publishing-platforms.

ᵛᶦ Mark McGurl, Everything and Less (London: Verso Books, 2021), 34.

ᵛᶦᶦ Brad Stone, Amazon Unbound (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021), 95.

ᵛᶦᶦᶦ Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism (Winchester: Zero Books, 2009), 44.

ᶦˣ Benjamin H. Bratton, The Stack (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2015), 50.

ˣ Thomas Poell, David B. Nieborg & Brooke Erin Duffy, Platforms and Cultural Production (New York: Wiley, 2021), 39-40.

ˣᶦ Chris Anderson: quoted in Antony Bryant & Uzma Raja, “In the Realm of Big Data,” First Monday, Vol. 19, No. 2 (2014). https://firstmonday.org/article/view/4991/3822.

ˣᶦᶦ Todd Bishop, “How Amazon Ended Up with Too Much Warehouse Space—and What It’s Planning to Do Next,” Geek Wire, 28 April 2022. https://www.geekwire.com/2022/how-amazon-ended-up-with-too-muchwarehouse-space-and-what-its-planning-to-do-next.

ˣᶦᶦᶦ Sara Lebow, “Amazon Will Capture Nearly 40% of the US Ecommerce Market,” Insider Intelligence, 23 March 2022. https://www.insiderintelligence.com/content/amazon-us-ecommerce-market.

ˣᶦᵛ Matthew Gooding, “Public Cloud Spending Grows 26% as AWS, Azure and Google Cloud Cash In,” Tech Monitor, 5 August 2022. https://techmonitor.ai/technology/cloud/public-cloud-revenue-aws-azure-googlecloud.

ˣᵛ Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (London: Profile books, 2019), 19.

ˣᵛᶦ Barry Libert, Megan Beck & Thomas H. Davenport. “Self-Driving Companies Are Coming,” MIT Sloan Management Review, 29 August 2019. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/self-driving-companies-are-coming.

ˣᵛᶦᶦ Bryant & Raja, “In the Realm of Big Data.”

ˣᵛᶦᶦᶦ Jeff Bezos, “Big Winners Pay for Many Experiments (2015)” in Invent and Wander (Harvard: Harvard Business Press, 2020).

ˣᶦˣ Jeff Bezos, “Fundamental Tools (2010)” in Invent and Wander.

ˣˣ Amazon, “Leadership Principles,” Amazon Jobs (2022). https://www.amazon.jobs/en-gb/principles.

ˣˣᶦ Stone, Amazon Unbound, 170.

ˣˣᶦᶦ Jeff Bezos, ““A Team of Missionaries (2007)” in Invent and Wander.

ˣˣᶦᶦᶦ Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 2.

ˣˣᶦᵛ Philip W. Anderson, “More Is Different,” Science, Vol. 177, No. 4047 (1972), 393.

ˣˣᵛ Chris Anderson, “The End of Theory: The Data Deluge Makes the Scientific Method Obsolete,” Wired, 23 June 2008. https://www.wired.com/2008/06/pb-theory.

ˣˣᵛᶦ Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1958), 322.

ˣˣᵛᶦᶦ Tarleton Gillespie, Custodians of the Internet (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018).

ˣˣᵛᶦᶦᶦ Natasha Dow Schüll, Addiction by Design (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 7.

best looking sub on the stack and as usual beautifully written